The 'Netflix Pill' Is Your Binge-Watching Future

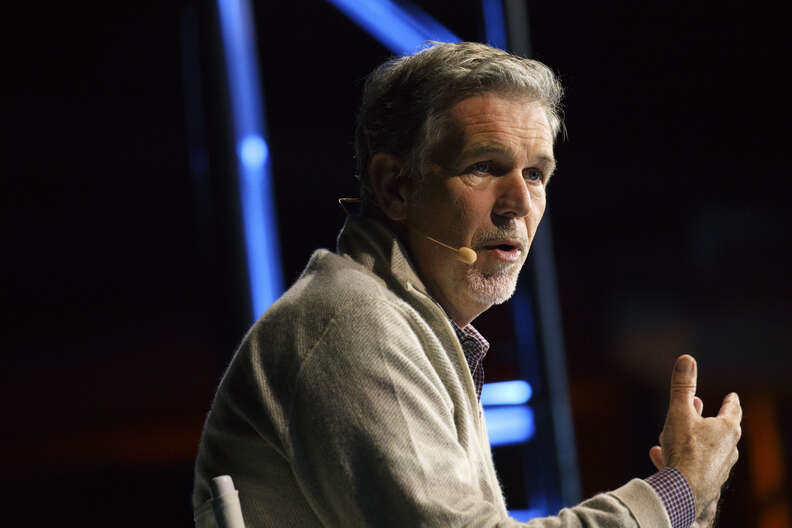

Like any Silicon Valley pioneer, Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, spends part of his life in the future. Which is why, in fall of 2016, he took the stage of a Laguna Beach technology conference to open a few new doors of perception. "The ultimate challenge for us will be can we figure out what that new form of entertainment is," he mused, wondering what would become of his eyeball-dominating streaming service. "Is it VR? Is it gaming? Is it AR? Is it pharmacological?"

Pharmacological? The final question piqued the interest of tech writers and cut through a storm of political coverage. "Netflix boss imagines replacing movies and TV shows with entertainment drugs," read a headline on The Verge. Time's angle took a more apocalyptic approach: "Netflix's CEO Says Entertainment Pills Could Make Movies and TV Obsolete." Everyone made "Netflix and pill" jokes.

To date, Hastings has yet to expand on his comments (through a Netflix representative, he declined to speak with Thrillist for this article) but the single word spoke volumes, especially because it was so out of place: Conversations about the "future" of television often feature the same buzzwords ("peak TV," "the great unbundling") and the array of alt-TV services (Netflix, Amazon, Hulu).

But Hastings' offhand speculation imagines a science-fiction-like future where entertainment could be digested on a literal level. Imagine a pill whisking you away to the world of Avatar or into the gaming playfield of BioShock like a new-age VR helmet. A Black Mirror setup or an actual future? Could the human body -- not Netflix or Snapchat or virtual reality -- be the next great platform?

To Hastings, our pharmacological, binge-tripping future may seem closer to reality because of Netflix HQ's location: Silicon Valley. Unlike science professionals, aspiring tech innovators, budding entrepreneurs, and hungry investors on the West Coast are known for "disrupting" at a different pace. The body is in their crosshairs.

Geoffrey Woo, the 29-year-old CEO and co-founder of Nootrobox, a startup that sells "smart drugs" made of ingredients the FDA recognizes as safe, was well aware of Hastings' comments when I spoke to him. "I think it's in the realm of possibility -- probably not launching tomorrow -- but I think very real," he says. "One thing we've been talking about and thinking about a lot [at Nootrobox] is humans as the next platform. If computing was the dominant innovation platform of the last few decades, then the human body as a platform will be where a lot of interesting things will happen in the near future."

Woo is, as a Bloomberg article dubbed him, a "bro scientist" attempting to sell real-world versions of the Limitless drug to intellectual strivers looking for a competitive mental edge. Similar nootropic supplements have become favorites of both startup workhorses and fringe figures like Alex Jones, who pushes Brain Force, his own Infowars-branded pill. Last year, Woo and his partner Michael Brand appeared on an episode of Shark Tank asking for a $40 million valuation -- the highest in the history of the show -- and got turned down. ("You came in and you gave us sugar cubes," said one judge.) Despite the public setback, Woo later told Business Insider they had six times more orders the weekend after they appeared on the show than they had at the same time a month before.

"If people wanted to be extra-scared, they could have a psychoactive compound."

As someone who works in the field of "biohacking," Woo is confident that the human body is the next frontier for technological innovation, which would also include entertainment. He not only imagines a way for drugs to carefully modulate neurotransmitters to create audio and visual reactions, but also sees a future where these drugs would be tailored to your specific genome. More personalized than your Netflix queue, these pills would be designed for your specific desires and needs. If your body wanted more Narcos, you'd get more Narcos.

Woo emphasizes that safety would be a primary concern. But once the science and the data are there, he believes the success of such a product would be about framing the use of it within a ritual that already exists. He compares it to the way bodybuilders and athletes might take supplements before working out. Why not work a "tailored nootropic" or "psychoactive stack" into your nightly viewing experience?

"I can imagine that if people wanted to be extra-scared, they could have a psychoactive compound that potentiates those neurons," he says. "You want to really accentuate feelings of adventure, you could accentuate other neurons that associated those kind of emotions -- or sadness."

Silicon Valley thought experiments can spark lively conversations, but acceptable scientific research standards have a voice, too. Dr. Charles Grob, the author of Hallucinogens: A Reader, is skeptical about an "entertainment pill" becoming a mainstream product anytime soon. After decades studying the effects of substances like ayahuasca, MDMA, and psilocybin, the UCLA professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral science has a deeper understanding of psychedelic drugs than the starry-eyed enthusiasts envisioning "pharmacological" forms of entertainment.

As he tells me over the phone, he was in college in the late '60s when these mind-altering drugs broke through into American youth culture. It wasn't like a quiet afternoon of binge-watching.

"I may be missing something here," he says when I explain Hastings' comments to him. "I've been doing this for decades, including at a time when it was virtually unheard of that this research was being done. So, I'm way out there. But on the other hand, I've gotten older and I've become a bit more conservative and cautious in my outlook."

He has reason to be: As Michael Pollan chronicled in a revelatory 2015 New Yorker article about psychedelic research, an "exuberance about psychedelics" during the 1960s created a political backlash that made it nearly impossible to conduct legal research that might assist patients with cancer, depression, PTSD, alcoholism, and other conditions. The signing of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970 by President Nixon made the use of psychedelics by medical professionals even more difficult. Twenty years later, Dr. Grob, along with colleagues at Johns Hopkins, NYU, and the University of New Mexico, brought these substances out of the shadows, one test at a time.

While Dr. Grob's and others' research has revealed a world of potential for psychedelics, they're still a long way from appearing at your pharmacy, let alone legally in front of your TV. Scientists and trained handlers conduct psychedelic experiments in controlled environments: Safety is key, which means careful screening, observed trips, and strict regulations. A "Netflix pill" would have to provide the type of consistent, reliable user-experience that would appeal to both thrill-seeking teenagers and risk-averse grandparents in order to become a reality. There would be no room for error. No one wants a bad trip to the world of Santa Clarita Diet after a rough day at the office.

The stigma against psychedelic drugs is certainly fading, now that magazines like Rolling Stone publish lengthy articles on the subject, books like Ayelet Waldman's new memoir about microdosing receive positive coverage in the New York Times, and movies like Noah Baumbach's While We're Young find comedy in aging hipsters attending an ayahuasca ceremony. And yet, there remains a skepticism around the subject -- a recent Times op-ed by clinical psychiatry professor Richard A. Friedman fears the hasty embrace of psychedelics could be catastrophic -- and a lack of public discussion about the potential medical benefits of these substances. The mass panic of the '60s still lingers, and would be a major hurdle to overcome for recreational "entertainment" use to become commonplace.

No one wants a bad trip to the world of Santa Clarita Diet.

Hastings' "entertainment pill" is intended to compete with blockbusters like Star Wars, The Fast and the Furious, or Game of Thrones. Believing in it requires a hopeful outlook of which the medical professionals I spoke with expressed their own skepticism. Dr. James Fadiman is a name you'll find in almost everyarticle about microdosing, the practice of absorbing small dosages of LSD to treat anxiety. But the 77-year-old psychologist and writer doesn't see much value in Hastings' statements. "His comments were silly but not much else," he wrote me in an email. "Since the invention of beer, there have been ways to entertain oneself in an altered state."

He's right. For ages, people have paired their drug of choice with specific pieces of art to create emotional reactions. Even professionals combine the two. Grob uses music in his trials, selecting specific playlists to facilitate a peaceful experience for his patients. A Brazilian subject in one of his ayahuasca studies envisioned himself traveling down a river as a melody guided his canoe.

Like Netflix's theoretical, medicated subscribers, Grob's patients experience "narrative." But it's intensely personal -- not the fuel for watercooler talk. "People often report visions with thematic content," he explains. "But generally [the visions] pertain to very important issues that they're working on that reflect their life events and where they're at and the challenges they're facing." Much of Grob's work is concerned with readying people for these journeys, helping to provide a safe trip. It's serious business. "I don't see it on the same level as just popping in a DVD on a Saturday night and watching a movie."

There's already a place where these technological leaps are a reality: the world of science fiction, which has shown an oft-bleak interest in experimental drug use for decades. English novelist Aldous Huxley, the writer of dystopian classic Brave New World, chronicled his own experiences with mescaline in the 1954 nonfiction title The Doors of Perception. In the '60s and '70s, sci-fi novelist Philip K. Dick wrote mind-expanding cult favorites like A Scanner Darkly and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which imagined drugs with names like Can-D, Chew-Z, and Substance D. In the '90s, the Wachowskis' action blockbuster The Matrix chiseled these concepts down to a stark binary: red pill or blue pill. Truth or lies. Reality or illusion.

Now, Jeff VanderMeer, the author of the acclaimed Southern Reach Trilogy and co-editor of The Big Book of Science Fiction, carries on the tradition of thinking about the ways technology interacts with our bodies and the environment around us. His latest novel, Borne, which arrives April 25, is about a young woman living in a hollowed-out city littered with the debris of a fallen biotech firm called the Company. While scavenging, she finds a green lump called Borne that could be plant, animal, or something else entirely.

VanderMeer has been thinking about these questions for decades, and like many before him, he's come to some imaginative (and troubling) conclusions.

"Fundamentally, we're about eliminating loneliness and boredom."

"I used to work in the tech industry for a software company," he writes via email. "My biggest complaint about tech companies thinking about the body as a potential platform for innovation is the technophilia seems unmitigated by asking the tough questions. Which is to say, it's not being a Luddite to say we don't yet understand how de-linking ourselves from the natural world hurts us. We don't have a complete science of it. And many of these innovations are really further ways to wall yourself off from lived-in experience in the moment and from the natural world."

Despite our quantitative devotion to Netflix -- in 2015, Americans averaged one hour and 33 minutes on the service per day -- VanderMeer wonders if anyone really wants an all-encompassing entertainment experience, and if immersion should be the goal. Do we really want to "live" an episode of Breaking Bad? As David Foster Wallace wrote about television in his 1993 essay "E. Unibus Pluram," the medium's greatest appeal is that it "engages without demanding." The passivity is essential.

There's also the question of what the Netflix pill would mean for writers, artists, and storytellers. Instead of TV writers rooms, would creative-types in sneakers toss around story ideas in a hi-tech biolab wearing white coats? It's tough to picture. "I work with words but in my head I see visions," says VanderMeer when asked about the possibility of an industry-wide upheaval. "I have a very tactile imagination that is then expressed through sentences and paragraphs. But if everything shifted, for me personally, I’d just shift over to the new form of storytelling."

The Netflix pill could also come and go. VanderMeer cites the regulatory oversight of the FDA and FCC, the fading popularity of 3D movies, and the slow acceptance of virtual-reality technology as potential reasons why the futurist fantasy would remain just that. Producing such a product really depends on what areas of study giant companies like Netflix, Google, and Facebook decide to pursue. What type of future are they trying to create?

Hastings articulated his mission on that stage back in October. "Fundamentally, we're about eliminating loneliness and boredom, and those are very serious human issues," he said. "They're not as big as cancer, I'll grant you that. But they're big issues in terms of human life. So what we focus on is how do we reduce loneliness and boredom. And that's what entertainment has always been."

A life free of boredom and loneliness is an unnervingly utopian vision of the future that doesn't sound much like life at all. Does it? Works of art -- whether they're science-fiction novels, psychedelic rock songs, or television shows where Kevin Spacey talks to the camera -- alleviate loneliness and boredom. They can't destroy them. I'd like to think that researchers like Dr. Grob, writers like Jeff VanderMeer, and even an entrepreneur like Geoffrey Woo would acknowledge that their work can't "eliminate" these basic parts of the human condition.

The moderator of the event perhaps sensed the slightly troubling, overambitious quality of Hastings' words. He pushed back against the CEO for a second, asking if he was serious. Was he actually trying to end loneliness? Is that really what fueled him and his enormous company as they designed the future of entertainment, pharmacological or not? "We take in money and out comes joy," Hastings said from the stage. "We think of ourselves as alchemists."

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email, and get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.